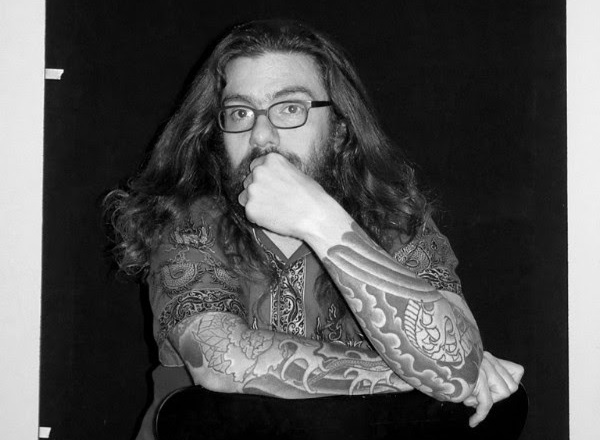

Photo by: Tom Gabriel Fischer

Former Celtic Frost/Hellhammer bassist Martin Eric Ain passed away last week of a suspected heart attack. Ex-Celtic Frost frontman Tom Gabriel Fischer – who currently fronts Triptykon – has shared an obituary that he wrote for Ain. He says:

“I have had to draft a disconcerting number of obituaries in recent years, mourning the loss of individuals who were either very close to me or of distinct importance to my life. But this obituary is by far the most difficult one to write.

Because Martin Eric Ain was unique beyond any description.

Martin was a part of me, and I was a part of him. Our lives were intertwined in a symbiosis that, at times, almost resembled a marriage, and yet our relationship was of an intricate nature and frequently fraught by disagreements. We both had a substantial impact on the development of each other’s path, and we both owed the escape from the fetters of the environment that defined our teenage years to each other’s existence.

I first met Martin around the time Hellhammer recorded the Triumph Of Death demo in 1983, when Steve Warrior and I would spend our Saturday nights at the then popular “Heavy Metal discos”. One of these events was called Quo Vadis, and it took place where Martin’s lived, in the village of Wallisellen, Switzerland. When I interviewed him for my second book, In September of 2007, Martin recalled:

‘The first time I saw Tom and Steve Warrior, they were part of a group of four or five metal fans, headbanging in unison while the non-metal crowd stood around them in a circle, staring. They walked as a leather-clad wall, and everybody got out of their way. It radiated power and violence, and I was extremely impressed.

We were in awe of these guys. They had arrived wearing sunglasses, and their jackets were covered with logos and patches of obscure bands which we had never heard of. They wore boots, leather jackets, bullet belts, studded armbands, and even studded gaiters. They all had long hair and were three or four years older than us and therefore obviously further along than we were. It totally blew our minds. It was like seeing members of Motörhead or Judas Priest standing in front of us. They looked like an album cover.

All of a sudden, there was a radical band within our field of existence. My parents were scared that Tom would seduce us into a life of alcohol abuse, drugs, and other illegal activities. They never recognized the actual threat which emanated from him. Just like so many people, they failed to recognize the power of this music. They perceived heavy metal as some asinine phase, as mere noise; they thought that nobody would ever take any of this seriously. They completely missed the fact that the music led to a radicalization inside of me and to the desire to define my life with music.’

Martin and I soon began to develop a close friendship. We spent uncounted nights discovering music together, discussing books, history, religion, occultism, or art, and then one of us would have to either bicycle or walk home to his own village, through pitch black forests at some ungodly hour. Martin’s intelligence, horizon, and vision were truly remarkable. I suppose it was only a question of time before we would begin to create music together, but Martin initially lacked the confidence and hesitated. Instead, he adopted the alias of “Mart Jeckyl” and began to support Hellhammer in a managerial role, supplying us with memos that detailed how we could improve our concept, image, and lyrics. He was only 16 at the time!

By the time Hellhammer produced the final demo that resulted in our first record deal, Martin was a co-author of some of our lyrics and sang some backing vocals on it. And then he finally became the bassist for good. The development of the group became fierce, and only five months later, we felt the need to drastically expand the scope of our alliance by starting from scratch, with a new project. This was the birth of Celtic Frost, during the night from May 31 to June 1, 1984.

Martin was one of the very few people who were prepared to embark on this journey with me, uncompromisingly and against significant opposition, unlike many others who only supplied hollow talk and then withered away. Completely self-thought, Martin became a superb and vastly original bassist with an almost uncanny ability to learn songs very quickly. And even though he initially wrote hardly any music, his many other contributions to the group were just as important. Celtic Frost’s uniqueness depended heavily on our creative collaboration, as I would inadvertently – and foolishly – prove a few years later. In the course of the 34 years we knew each other, we would jointly experience and survive just about any situation one might be able to imagine, not least the destruction of Celtic Frost – twice!

The partnership with Martin Eric Ain was instrumental in enabling me to fulfil my ardent teenage dream of becoming a musician. Determining Martin’s own deeper motivation to pursue this quest is more difficult, however. I think his was more a sense of rebellion against the surroundings in which he grew up, and once this was accomplished, the musical path no longer had the same importance to him. He subsequently became a very intuitive and thriving entrepreneur and embarked on ventures that often were blatantly at odds with the values he so fervently stood for during his youth.

It was much the same after we reunited Celtic Frost in 2001, recorded the triumphant Monotheist album, and toured the world. Whereas Martin had initially agreed with me that the reunion would be a long-term venture, he confided to me towards the end of the tour that he felt we had sufficiently proven ourselves, and that he did not see a necessity for another album, at least not in the foreseeable future. Moreover, he was weary of the strains of touring and maintaining a band in a vastly changed modern musical landscape versus the comparatively comfortable and lucrative life he led in Zurich managing clubs and bars. His attention was already elsewhere, and I realized that the reunion for him, again, had served a different purpose.

Martin had a complex personality, coloured by contradictions and indulgence (and I am sure he would describe me exactly the same). He frequently accused me of exorbitance (and undoubtedly had a point), and yet he himself pursued immoderation, if on different levels. He knew, of course, and once labelled his acquisitiveness ‘pathological’. He resorted to verboseness to mask insecurities and his discomfort about revealing too much about his emotions. He was the best and most amazingly generous friend anybody could wish for, as those fortunate enough to know him closely will confirm. And yet, in an interview published in Switzerland in January of 2010, he himself asserted: ‘I don’t like people who embark on ego trips that end up hurting others, although I cannot deny being guilty of exactly such behaviour.’

He would often choose the path of least resistance or refrain from taking a side instead of acting decisively to quench the mounting band-internal conflicts. He watched Celtic Frost’s protracted and painful self-destruction, only to tell me, a month after my exit from the group, that if he would have spoken up, the band could have been saved. But by that time, Martin had grown so tired of the dysfunctional group that I became convinced he was secretly relieved that I left, because it spared him of having to quit himself. But I often had the feeling that part of him felt a nagging sense of guilt ever since.

I am no stranger to the passing of a beloved human being, and death itself is not an abstract or intimidating concept to me. But the fact that a friend of such profound significance has irrevocably been taken from his life is exceptionally painful. I am very glad that I instigated the Celtic Frost reunion in 2001, and that I thus was granted to experience Martin as a newly mature and astonishingly capable musician and songwriter. Notwithstanding the strenuous work involved, touring the world with him one final time was a privilege. In fact, every minute spent in Martin’s company was a privilege, and this includes our last meeting over coffee, a short time before his death.

Martin’s passing affects me deeply. The world will never be the same without him. His death signifies the end of an era, both for our music and on a profoundly personal level. I, the older one, had always subconsciously expected him to survive me and become the custodian of the legacy we created together. The shock about his untimely death, the pain, and the sense of loneliness and loss are unbearable and insurmountable.

Martin, I will miss you deeply until my days, too, will come to an end.”

– Tom Gabriel Fischer